Most Linux distributions, including Fedora Core, provide two forms of service access control: TCP wrappers and iptables. I use the term access control and not firewalling because TCP wrappers should really not be referred to as a firewall per se. The older TCP wrappers offers centralized daemon host access control in one nice and easy to edit file. It can be configured to monitor incoming requests for a range of daemons, works in tandem with xinetd, and changes to it are instantly applied. TCP wrappers is somewhat insecure if used on an untrusted network, is not very powerful, and so should only really be used on trusted networks or where very specific requirements demand it. iptables is the newer Linux form of true firewalling. Its technology is generally referred to as netfilter, as it exists on several OS platforms. iptables itself is a packet/kernel-level, system-wide, user space control system that allows control of the real-time network filter rule sets in the running kernel. These rules allow for multinetwork SPI, control, modification, and redirection. It is much more powerful than TCP wrappers, but can also be more complex to use. It can be used on trusted or untrusted networks and so makes a perfect multihome, multinetwork firewall/router solution.

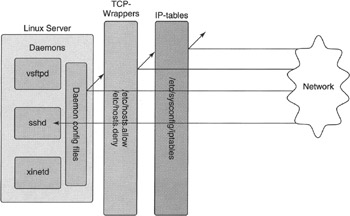

Figure 11-3 shows how iptables and TCP wrappers (on top of various daemon configuration files for access control security) together form various levels of service access control, or what is often loosely referred to as firewalling. The various levels of security shown in this figure are illustrated in the order that incoming network client requests encounter them.

As the network client requests come in through the network card, they encounter the iptables portion of the kernel. In Red Hat and Fedora Core systems, this config is controlled from the /etc/sysconfig/iptables file. If the clients pass these tables of filters and rule-chains, they then pass through to the TCP wrappers level of the system, assuming that the requested daemon is compiled with TCP wrapper's libwrap support. If the service or daemon has libwrap support compiled in, and thus can even be controlled by TCP wrappers, TCP wrappers then allows the client requests to pass or blocks them per the allow/deny files. The final layer of network client restriction is sometimes configurable by the daemon via the daemon's own internal configuration file (for example, Apache = httpd.conf and FTP = vsftpd.conf). These last two levels of TCP wrappers and daemon level config file service security are not considered true firewall quality forms of network protection, but are usually just used as a convenient way for an administrator to allow or deny daemon-level access on a trusted network. Although many administrators sometimes use wrappers and deamon config allow/deny settings on untrusted networks (such as the Internet), such configurations are not recommended. These older and less secure forms of access control only form a quick and easy service/host access system for trusted networks and should really not be considered a real firewall.

As previously stated, TCP wrappers does not actually function as a firewall. Instead, it is a simple and effective application-level daemon wrapper. TCP wrappers is a set of libraries that xinet.d and other daemons are compiled against. Among other things, it lets you form simple service/host-based access control lists (ACLs) based rule sets that control which hosts or networks are allowed to access your various daemons. Daemons that are compiled against the libwrap library like this can then be controlled through the host access control files /etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny.

Several, but not all, of the network daemons in Fedora Core and other Linux distributions are already compiled against libwrap. To determine which of your daemons have libwrap support, locate them with the following command:

# egrep libwrap /sbin/* /usr/sbin/*| sort Binary file /usr/sbin/in.tftpd matches Binary file /usr/sbin/mailstats matches Binary file /usr/sbin/makemap matches Binary file /usr/sbin/praliases matches Binary file /usr/sbin/rpc.rquotad matches Binary file /usr/sbin/sendmail.sendmail matches Binary file /usr/sbin/smrsh matches Binary file /usr/sbin/snmpd matches Binary file /usr/sbin/snmptrapd matches Binary file /usr/sbin/sshd matches Binary file /usr/sbin/stunnel matches Binary file /usr/sbin/vsftpd matches Binary file /usr/sbin/xinetd matches

Because they have libwrap support, these daemons should be able to be controlled through the /etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny files.

Is TCP wrappers the appropriate service solution for you? If you're running a services-based server (from which services are being offered) on a trusted network, and all of your running daemons use libwrap, and you're already protected by a full-blown internetwork firewall, then TCP wrappers can be a quick and simple way for you to control which machines and networks have access to services on your server. If you need more security on your services-based server, more feature-rich or complex firewalling rules like session tracking, or stateful inspection, or you're running a network firewall in a multiple network card (multi-home) NAT configuration, then you definitely need the strength of iptables.

Remember, if you're just running a basic FTP or sendmail mail relay server or the like, then TCP wrappers can be used if you're on a trusted network. But a true firewall cannot, nor can it be used to limit access through a network firewall.

iptables is essentially the fourth generation of a packet filter system for the Linux kernel called netfilter. Packet filtering was originally released on BSD via ipfw and was integrated into the Linux kernel in version 2.0. When the 2.2 version of the Linux kernel was released, packet filtering was controlled by a user-space tool, ipchains. With the 2.4 and newer kernels, we have the modern iptables tool and related kernel modules that offer complete control over almost every piece of network data that comes into or leaves our networks.

To summarize, iptables is a stateful packet network control, filtering, modification, and redirection system that is one of the more advanced and readily available implementations of netfilter available today. Plus, it's free. Unfortunately, iptables can be somewhat difficult to learn for the uninitiated, or for those who do not have a firm grip on the packet-level operations of networking protocols, especially so if you want to control iptables manually via flat configuration files or scripts rather than via a graphical tool. Some people find it easier to use such graphical control tools to do stuff, then look at the iptable config output, and learn the inner workings of iptables this way, while others prefer to just dive right into the command line syntax. In this chapter we mainly use the command line approach, but feel free to download one of the graphic tools discussed later and check out the GUI approach.

At its most basic level, a packet filter is a program that scans network traffic as it flows through the system and then makes decisions about each packet. Based on the filters or rule tables that the administrator configures, iptables can DROP (discard) or ACCEPT a given packet. In addition, iptables offers more sophisticated tools like Network Address Translation, masquerading, and the ability to forward packets to other machines or networks. This is why Linux and iptables is such a perfect fit for high-powered firewall configurations, and why we're starting to see this combination secretly appear in several commercial and SOHO firewall products such as the SnapGear PCI635 (www.cyberguard.com/snapgear/pci635.html), theProWall (www.protectix.com/prowallspecs.html), and others. It's powerful, small, and cheap.