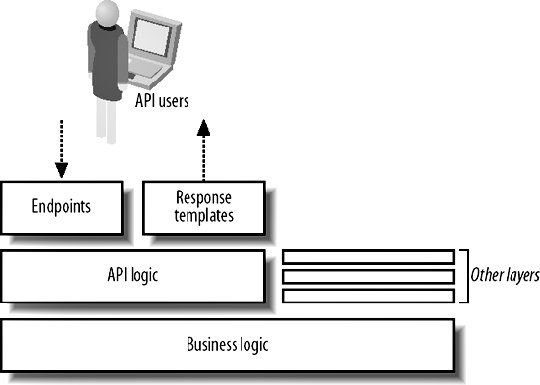

11.3. Web ServicesWeb services are starting to get fairly popular but are not often well understood. When we talk about web services, we mean interfaces to data offered over HTTP, designed to be used programmatically. With this loose definition, RSS feeds appear to a be a web servicethey share data across HTTP in a format intended for parsing by software rather than humans. Indeed, data feeds are a form of web service, although they're not usually included in such discussions. Web services has become a label for XML sent over HTTP with read and write capabilities, but this is not the entire picture. While HTTP does always sit at the core (putting the "web" in "web services"), we don't necessarily need to use XML, nor do we need to provide methods to write data. Many web services only allow querying and reading of data. Inside our own application, there are nearly always useful web services we can export. If we're collecting data together for users in some way, allowing the users to access their own data programmatically, either via RSS or some dedicated API, will be beneficial to the user. When exposing web services, it's a mistake to think we're just catering to nerds. While only power users will touch the services directly, services allow third-party developers to build applications that interoperate with your product. This can range from adding support to an existing application, to creating open source applications based around your application, to creating commercial products that use your services (presuming you allow such things). Allowing third-party application development can be good for your application in several ways. If you already have auxiliary applications built around your core application, third-party developers can help you cover more platforms (for instance, building Mac and Linux versions of your applications). For the applications you already provide, third-party developers can improve on them, allowing you to provide better service to your users without having to put in the development work yourself. Third-party application developers can also create applications around your core service that you hadn't previously thought of, or wouldn't have spent the time doing. All of these applications are great for providing extra utility to users and driving user adoption and loyalty. Any operation we perform within our core application can be exported via an API. If we have a discussion forum component, we might provide API methods for getting a list of topics, getting a list of replies in a topic, getting a user profile, creating a new topic, replying to an existing topic, editing a reply or topic, deleting a reply or topic, and so on. Any action within your application can be ripe for export. That doesn't mean you have to go all-out straight away and export every feature you have to the public. You can start out by exposing just the most important parts of your application. In our example discussion forum, we can first export the reading function, since that allows us to build interesting and useful applications, without dealing with the issues involved with authentication. As with everything in our application, we'd like to be able to support things as easily as possible, with maximum gain for minimum effort. Again, with our layered architecture we can simply build an API interface on top of our existing business logic layers, as shown in Figure 11-5. Figure 11-5. The API stack We'll talk more about endpoints and responses in a moment when we look at API transports, but what's important here is that we're always building on top of our firm base. We never have to build new core logic; like mobile content delivery, APIs for web services are just another set of presentation layers sitting on top of our application core. By providing a public API into our core services, we're not just making them available to third parties, but also more available to ourselves. Once we have these services, we can start to use them for our own applications. Any desktop applications that we provide to users will (presumably) need some way to communicate back with the application mothership. We can do this using our own public API, eating our own dog food. This approach ensures that the APIs we offer are useful and usable. Nobody knows better what data and methods need to be exported in an API than somebody building applications on top of it. We can also use our API to power any Ajax (asynchronous JavaScript and XML) components of our application. We haven't talked about Ajax so far because of its client-side nature, but it presents some interesting issues at the backend. To be able to use Ajax at the frontend, we need something at the backend for it to request asynchronously. By using public APIs to power Ajax interaction, we can avoid creating two systems to do the same task, and leverage existing work. The development of Ajax components also becomes faster and easier when you're building against a well-defined and documented API, so we can separate the layers well, rather than the mash of logic that Ajax applications can become. To drive public adoption of your API and allow developers to hit the ground running, the trend has been to provide and elicit developers to work on API "kits." API kits are typically modules that you can plug in to programming languages to allow access to your API without any knowledge of how the API transport or encoding is implemented. Providing API kits will greatly encourage adoption as the barrier to entry for developers drops. For Flickr, the Flickr-Tools Perl package by Nuno Nunes allows you to get a list of photosets belonging to a user in a couple of lines without having to know anything about the API. In fact, you can't tell from the code that we're dealing with a remote service:

use Flickr::Person;

use Flickr::Photoset;

my $person = Flickr::Person->new($flickr_api_key);

$person->find({username => 'bees'});

for my $set($person->photosets){

print "Photoset: ".$set->getInfo->{title}."\n";

}

Finding out what bindings your developers might want can be very important in driving API adoption. By providing the core set of language support (PHP, Perl, Python, .NET, and Java), you can encourage people building with more outlandish languages and applications to build their own API kits, or at least learn from the code in the provided kits. When working with remote services, nothing is as useful as a reference implementation. |